The rise of the nomads

The Russian steppe (sometimes just referred to as the steppe), is a vast swathe of land stretching from the Black Sea to encompass the western half of the northern Caucasian plain, and extends northeast across the lower Volga, the southern Urals and the southern parts of western Siberia. It goes through Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Western Russia, Siberia, Kazakhstan, Xinjiang, Mongolia, and Manchuria. It is the largest temperate grassland in the world and reaches almost one-fifth of the way around the planet. The steppe has historically been one of the most important routes for travel and trade. The flat expanse provides an ideal route between Asia and Europe. Caravans of horses, donkeys, and camels have travelled the Eurasian steppe for thousands of years. The most famous trade route on the steppe is the Silk Road (a term coined by the German traveller, geographer, and scientist, Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833–1905) in 1877), connecting China, India, and Europe. The Silk Road was established around 200 BC and many Silk Road trade routes are still in use today.

The steppe is semi-arid, only getting 25–50 centimetres (10–20 inches) of rain each year. This is enough rain to support many kinds of grasses on the Eastern steppes like feather grasses (Stipa capillata), wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), fringed sagebrush (Artemisia frigida), false oat grass (Arrhenatherum elatius) and the Russian thistle (Kali tragus – better known in the US as “tumbleweeds”), but few grow taller than half a metre (20 inches). The western steppe is more humid so that small trees and shrubs can also grow, especially poplars and aspens, which sometimes cluster into small woods. This vast endless grassland is unsuitable for intensive farming and unable to support a dense population, so, historically, the thinly scattered population lived as small nomadic groups in tented encampments tending their cattle and sheep –they move as their herds need fresh pasture.

A study in 2014 also found that by the middle second millennium BC, these herders while in their seasonal camps in the mountains and deserts incorporated the cultivation of millet, wheat, barley and legumes into their subsistence strategy and may have had an integral role in transforming agriculture across Asia. These nomads have always had an almost enigmatic place in world history and from the late Bronze Age until the Middle Ages the steppe was home to a series of organised and highly influential empires, including the Xiongnu, the Scythians, the Sarmatians, the Hunnic Empire, the Göktürk Khaganate and the Mongol Empire. The climatic conditions of the steppe are harsh, with hot summers and freezing winters (average summer temperatures range from 21°C to 23°C and in winter, while mild by Russian standards, from -13°C to 0°C). These conditions bred a tough people. The men were skilled warriors, fighting with bows and arrows from their fast-moving ponies. So much so that the Scythians managed to repel Alexander the Great’s army, as well as a Persian invasion. The Greek historian, Herodotus (485–425 BC), described how Darius I (550–486 BC), king of Persia, led some 700,000 troops on to the Russian steppe in an effort to conquer the area. Outnumbered, the Scythians refused to meet their intruder head on but kept retreating, all the while engaging in guerrilla warfare. Darius was confused – how do you battle with people who won’t fight? – especially as there was nothing for him to conquer; just a seemingly unending grassland? Eventually, Darius did the only thing he could – he turned around and headed for home. The Scythians harried Darius and his troops all the way back to the Danube. Persia never again attempted to take the southern Russian steppe and the Scythians flourished for the next 100 years.

One of their allies during this encounter was the Sarmatians, who lived to the northeast of the Scythians and though they were kindred tribes they had a primary difference. Unlike the Scythians, who believed that women did not have much status in their society, their duties being purely domestic, the Sarmatian women were believed to be the descendants of the female warrior race the “Amazons”.

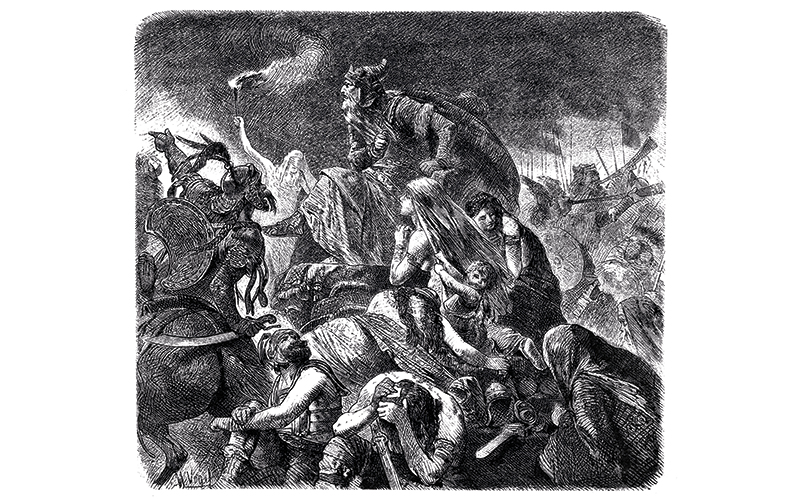

Illustration of Attila in the battle on the fields Catalaunian plains

According to Herodotus, the Greeks in Asia Minor defeated a tribe of warlike women, and sent them, as slaves, onto a ship. The women rebelled, took control of the ship and settled in a lowly populated area called Sarmatia, on the northern shores of the Black Sea. Although this was always considered to be a myth, recent excavations in southern Russia have discovered evidence of women warriors buried with weapons and contemporary records suggest that these women smoked cannabis, drank the powerful concoction of fermented mare’s milk called kumis, wore trousers (leg coverings are absolutely essential if you’re going to spend your life on horseback) and were heavily tattooed. Herodotus wrote that the female offspring, “have continued from that day to the present to observe their ancient [Amazon] customs, frequently hunting on horseback with their husbands; in war taking the field; and wearing the very same dress as the men... No girl shall wed till she has killed a man in battle”.

Rise of empires

Occasionally a leader would appear who unified the nomadic tribes. Attila the Hun was the ruler of the Hunnic Empire in Central and Eastern Europe from 434 AD until his death in 453 AD, consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans (an Iranian nomadic pastoral people) and Bulgars, among others. During his reign, he was one of the most feared enemies of the Roman Empire, before being beaten by Flavius Aetius (391–454 AD) at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. Hydatius (400–469 AD) wrote of the battle that almost 300,000 men had fallen including King Theoderic (390–451 AD, ruler of the Visigoths) who was fighting with the Romans. It is now thought that the migration of the Huns across the steppe into Europe may have also carried the plague. Certainly, DNA analysis of skeletons found on the Eurasian steppe recovered a strain of plague related to the one responsible for causing the Justinian Plague (541–542 AD), which may have killed as many as 25 million people. Also, Yersinia pestis DNA related to the Justinian pandemic has been found in a Hun skeleton from the Tian Shan mountains of Central Asia who died around 200AD, further back in the plague’s genetic “family tree”.

Bumin Qaghan (490–552 AD) brought together the first East Asian transcontinental empire, the Göktürk Khaganate stretching from Manchuria to the Black Sea. The Göktürkler(s) were a Turkic people of ancient Central Asia and under his leadership they became the main Turkic power in the region and took hold of the lucrative Silk Road trade during the sixth century. They rapidly expanded the empire to rule huge territories in north-western China, North Asia and Eastern Europe (as far west as the Crimea), but internal civil wars brought the empire to an end in 603 AD. Genghis Khan (birth name Temüjin 1162–1227 AD) rose from humble beginnings to establish the largest land empire in history. After uniting the nomadic tribes of the Mongolian plateau, he conquered huge chunks of central Asia and China. His descendants expanded the empire even further, advancing to such far-off places as Poland, Vietnam, Syria and Korea. At its peak, the Mongol Empire controlled between 11 and 12 million contiguous square miles – an area about the size of Africa.

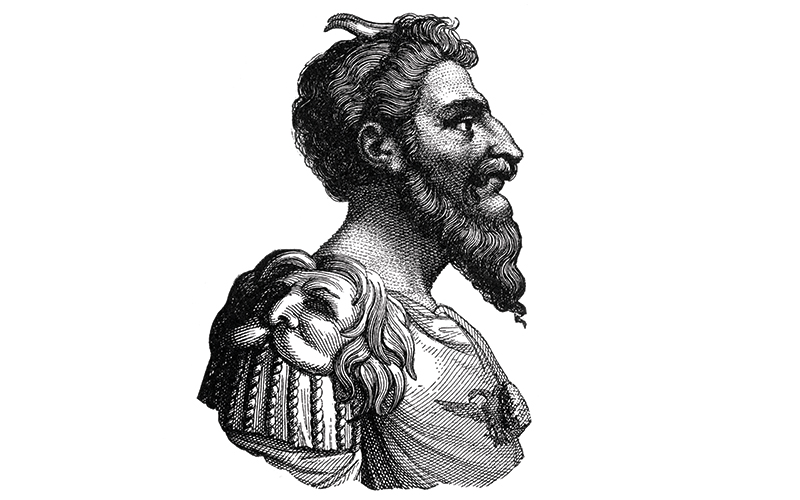

Engraved illustration of Attila the Hun, 434–453 AD

Medicine of the steppe

Recent studies suggest that although the Scythians had no written language, their goldsmiths were very skilled in depicting everyday life on gold vessels. And in 1983 Dr Charles Denko believed that the picture on a Scythian gold vessel (recovered from the Kul-oba burial mound in the district called Kurgans near Kerchin, Southern Russia) showed

a patient in consultation with his physician. More importantly, there were deformities of the hand and foot consistent with inflammatory arthropathy. So, it appears that the Scythians were aware of the rheumatic diseases that had previously been described by Hippocrates and Herodotus. Contemporary records suggest that the Scythians also had sufficient medical knowledge to perform sophisticated and successful manipulations on the human skull. They also perfected a scraping technique with bronze tools for an effective method for the prevention of wound infection, which resulted in a high survival rate after surgery. Herodotus also noted that the Scythians did not use water to clean themselves. A paste of cypress, cedar and frankincense was made, the body was plastered with it and left on for

a day. When this cast was removed, the revealed skin was clean, shiny and possessed a most pleasing aroma. It is not hard to imagine that being on the move constantly these nomadic tribes relied on local medicine and folk remedies. Traditional doctors were known by many names (Shaman, the Ocak folk healers, Kams or simply holy men) and quite often they relied on magic and spiritual powers to cure illness. They were called on to determine whether the illness was caused by natural means or because of malicious wishes. These folk healers were considered to be the wisest and the most respectable people in the society, in terms of materiality and morale. They would heal the sick and perform prophecy readings. There were, however, the Bariachis specialist Mongolian bone setters, who would manipulate bones back to their proper position, often without medicines, anaesthetics

or instruments. Bariachis were laypeople, without medical training, and were born into the job, following the family tradition.

The Mongol Empire, like others before it, assimilated cultures. It also took the medical knowledge of these people, adapted it to develop a new medical system and, at the same time, organised an exchange of knowledge between the different people in their empire, including Chinese, Korean, Tibetan, Indian, Uighur, Islamic, and Nestorian Christians. Despite its violent beginnings, Mongol dominance over Asia and the Middle-East ushered in a century of stability referred to as the Pax Mongolica, which enabled an unprecedented level of commercial, cultural, religious and scienti?c exchange across Eurasia and had a striking in?uence on the course of medical and surgical history in Asia and Western Europe. Genghis Khan always believed that there was strength through diversity, and the Mongol Khans directly encouraged the growth and exchange of medical knowledge throughout their Empire. Hospitals based on the Persian model, much like those of today, were established and teams of physicians sent from all corners of the empire to serve there. On their journeys throughout Asia, the Mongol Khans took with them a team of doctors (usually foreign) and their first role was to be the personal physicians of the Khans in case they required medical attention. The second was to observe and obtain any new medical knowledge from the various groups of people that they encountered. Finally, they were to also spread the medical knowledge that the Mongols had put together to the people they encountered.

Tumbleweed

Herbal remedies

During their travels the nomads collected and used herbs as medicine for diseases, illnesses and injuries. It was also believed that eating certain parts of wild animals that had potent spirits, such as wolves and even marmots, could help with certain ailments, too. Donkey meat was considered a good remedy for wind and depression, while bear paws helped increase someone’s resistance to cold temperatures. Foreign physicians who used herbs to treat illness were distinguished from the shamans by their name, otochi, which meant herb user or physician. It was borrowed from the Uighur word for physician, which was otachi. As Mongolian medicine began to transition to using herbs and other drugs and had the service of foreign doctors, the importance of shamans as medical healers began to decline. Contemporary records seem to suggest that any plant could be used as a medicine, provided it fulfilled the following criteria from a traditional healer or emchi: “All those flowers, on which butterflies sit, are ready medicine for various diseases. One can eat such flowers without any hesitation. A flower rejected by the butterflies is poisonous, but it can become medicine, when it is properly composed.”

Scythian figurine of moose

In 2013 the WHO published a report on the common medicinal plants used in traditional Mongolian medicine. The uses of medicinal plants have been passed from one generation to the next and without systematic documentation of the role of indigenous plants in Mongolia, we risk losing valuable knowledge. These are some of the plants mentioned in the report.

Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis) has been a staple ingredient in Chinese herbal medicine for many years. The major active constituent of liquorice root is glycyrrhizin (C42H62O16) and has been used in traditional medicine to help alleviate bronchitis, and gastritis. It also has been shown to produce an inhibitory effect on HBeAg secretion that imparts anti-HBV activity. Studies have also shown that glycyrrhizic acid induces inhibitory effects on hepatocyte apoptosis and liver fibrosis so its use as a traditional treatment for jaundice may have been prophetic.

Mission grass

Historically, Asiatic yarrow (Achillea asiatica Serg.), has been used to relieve a variety of ailments and contains apigenin-7-O-glucoside (C21H20O10). Recent studies have shown that it has both antifungal activity on Candida spp. and a cytotoxic effect on colon cancer cells. Traditionally it was used as an anti-inflammatory agent and for treating persistent fevers. The low-toxicity compound β-asarone (C12H16O3), has been isolated from the perennial herb Acorus calamus (sweet flag) with its bright triangular green leaves. Traditionally it was used as an anticonvulsant, but it also had antibacterial, nematocide and antifungal properties. Studies have now found that β-asarone can enhance the effectiveness of doxorubicin in the treatment of certain lymphomas. Black or stinking henbane (Hyoscyamus niger L.) is a large biennial, with leaves covered in soft curly hairs.

One of the active components is scopolamine (C17H21NO4), a medication used to treat motion sickness and postoperative nausea and vomiting. Traditionally, the plant and components were used as a sedative, an anticonvulsant, an analgesic, and anaesthetic.

Acorus calamus

Achillea asiatica

Glycyrrhiza acanthocarpa

Siberian barberry (Berberis sibirica) contains protoberberine alkaloids, particularly berberine. Studies have shown that berberine (molecular formula C20H19NO5), which has been used to treat diabetes for thousands of years, acts as an anti-hyperglycaemic agent. The leaves contain flavonoids and the fruit contains organic acids and ascorbic acid. It is thought that one of the main actions of berberine is to activate the enzyme AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which regulates metabolism. For the nomads it was used as a poison antidote, for treating diseases of the lymph and the eye, bile disorders, and overcoming diarrhoea.

The major active constituent of liquorice root is glycyrrhizin and has been used to help alleviate bronchitis, and gastritis

Adams rhododendron (Rhododendron adamsii Rehdes) or better known by its common name Sagan Dalya has been used in folk medicine of Russia and the indigenous tribes of Eastern Siberia for heart, nervous and stomach illnesses, as a diuretic, and to encourage sweating and lowering fevers. However, there was always a belief that the application of this plant acts holistically on the human body rather than on individual ailments. It is possible to use both the root and flowers of Meadow Cranesbill (Geranium pratense L.); the taste is both sweet and bitter.

It has been used for treating conjunctivitis and other eye diseases, as well as intestinal upsets like diarrhoea and dysentery.

Rough chervil (Chaerophyllum gracile Freyn. & Sint.) root was used because of its sedative effect and it enhances breathing. The root contains coumarin (C9H6O2), which is a colourless crystalline solid with a sweet odour resembling the scent of vanilla and a bitter taste. It is found in many plants, where it may serve as a chemical defence against predators.

Warfarin is a coumarin and is an extremely effective anticoagulant used to treat blood clots in cases of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. It can be also used to tey and prevent thrombosis in patients at high risk, such as in atrial fibrillation, heart attack and knee or hip surgeries.

Rough chervil root was used because of its sedative effect and it enhances breathing

And who would have believed that rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum), a member of the sorrel family, originally came from the steppes of Asia over 2000 years ago and grows in the wildin western and northwestern provinces of China. The name rhubarb comes from the Medieval Latin reubarbarum, literally meaning barbarian rhubarb. The ground-up root has been used as a purgative and, since it didn’t give people the stomach cramps of other purgatives, soon became a favourite in western countries as well. And it goes very nicely with custard!

Conclusions

The Eurasian steppe nomads maintained a symbiotic relationship with their environment for some 6000 years and there has been a substantial influence on Russian culture mostly by Slavic, Tatar-Turkic, Mongolian and Iranian people interaction.

The rise of nomadic states and empires led to horse domestication, spoke-wheeled chariots and cavalry warfare, early metal production, trade, and Indo-European languages. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries drastic changes happened across the steppe – there was an influx of people into the steppe zone, which led to a strong decline in nomadic pastoralism. When the settlers arrived they continued to practise forms of agriculture similar to those they used in their generally well-forested and well-watered homelands. They soon discovered, however, that the ploughing under the steppe’s grasslands and the unpredictable water supplies meant that the black soils alone were insufficient to ensure the desired harvests each year, quite often leading to famine. These farming practices have decreased substantially since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and as a result, many areas of the steppe are now undergoing secondary succession and a rewilding process to return them to their original habitat. And the nomads? These are highly threatened societies, but it has been estimated that there are three to six million Mongols living in China today. Most of them reside along the northern border with Russia and Mongolia in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR). A significant population are still full-time nomadic pastoralists, herding sheep, yaks, goats, horses, camels, and dogs, living in temporary structures we know as yurts. There are also the Dukha people and the Tsaatan reindeer herders of icy Northern Mongolia’s sub-arctic Khövsgöl Aimag region, a tiny subgroup of about 40 families living in symbiosis with their animals, moving up to 10 times a year. They want to preserve their traditions and eschew the trappings of a forced “development” while the steppe environment can still sustain them.

Stephen Mortlock is the Pathology Manager at the Nuffield Health, Guildford Hospital. To read this article with full references, visit thebiomedicalscientist.net